Supportive clinical evidence from sibling studies suggests that early intervention provides multiple opportunities to improve patient outcomes through disease-specific management and early initiation of ERT, if available.1–6

ERT, whether initiated early or later in life, has been shown to improve key clinical parameters, such as endurance and pulmonary measures, which are critical to quality of life, maintenance of ambulation, and activities of daily living.7,8

The new era of management for progressive, complex, genetic conditions, such as mucopolysaccharidosis (MPS) disorders, hinges on the efficient coordination of each patient’s healthcare team by a medical home.1

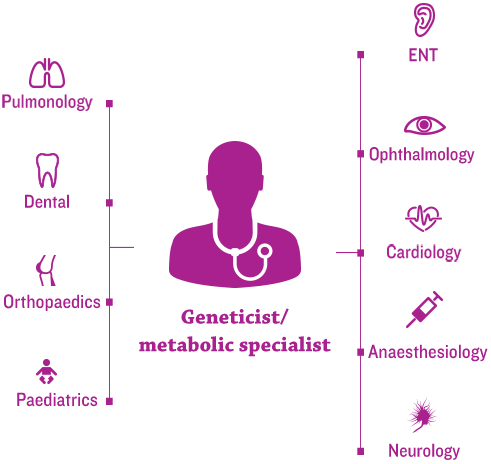

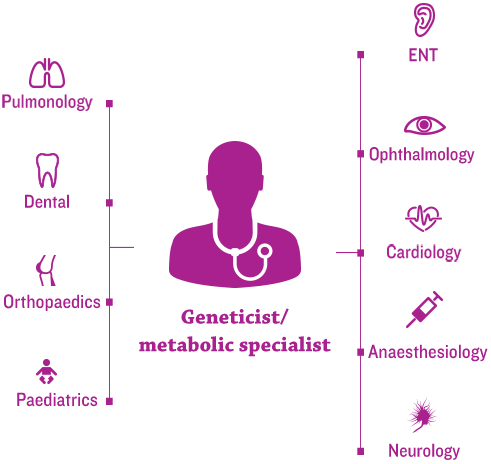

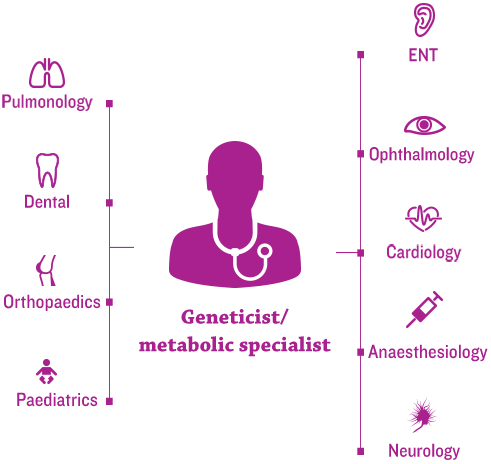

Geneticists and/or metabolic specialists are typically at the centre and help to coordinate multidisciplinary care and an individualised management plan.2,3

Given the nearly universal manifestation of musculoskeletal symptoms in patients with MPS, orthopaedists are essential members of the multidisciplinary medical team.4

Many MPS disorders have available management guidelines and speciality-specific consensus recommendations regarding lifelong management of MPS. Guidelines typically recommend the following:3,7

Early and ongoing assessments from a coordinated care team can improve patient outcomes and may help prevent irreversible damage.7

The following common musculoskeletal manifestations should be assessed and monitored:8,9

Similar musculoskeletal manifestations are seen in all types of MPS; in fact, it is usually other clinical manifestations that distinguish the MPS subtypes from one another. However, some notable differences are observed:8

Common musculoskeletal features of MPS by subtype are outlined below.

Skeletal complications are universal in all MPS disorders, though progression of these complications varies among patients. Prevalence of specific orthopaedic manifestations across MPS subtypes varies, as detailed in the table below.

The guidelines include the following overarching recommendations:3,11

A more comprehensive schedule of imaging assessments can be found below.

Initial and periodic annual assessments should be used to monitor musculoskeletal disease progression, determine if and when surgical interventions are needed, and provide guidance regarding increased frequency of evaluations. In particular, monitoring for spinal cord compression is critical.3,5

Spinal cord compression is common in certain types of MPS—particularly in Morquio A and MPS VI—and poses significant risk of mortality in these patient populations.3,12

The above example is related to Morquio A and is similar to considerations given across MPS disorders. The goals of neural axis imaging in Morquio A are as follows:12

Patients with MPS are at elevated risk of complications from anaesthetic and procedural sedation. When possible, general anaesthesia should be avoided and, when necessary, administered only by experienced anaesthesiologists.12,13

Of note, enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) can positively impact mobility and endurance, which could lower the threshold for orthopaedic surgery to facilitate a more active lifestyle.3

Frequency of assessments and involvement of specific specialists vary across the different MPS types. For patients with MPS diseases associated with primary neurodegenerative and cognitive complications, such as MPS I, II, and III, additional and regular neurobehavioural and psychiatric evaluations are recommended.7,14,15

In addition to speciality-specific assessments that should be done to facilitate positive long-term outcomes for patients with MPS, important steps can be taken by the coordinating physician, typically the geneticist and/or metabolic specialist, related to general health. Their role in educating other healthcare professionals (e.g. dentists, physiotherapists, paediatricians, family doctors) and families about the disease and general management strategies is critical and should include the following:

Speciality-specific assessments, as well as regular physical examinations and overall health interventions, should follow recommended guidelines, which may vary among MPS subtypes.3

Improvements in the treatment of MPS disorders are contributing to long-term outcomes for patients, necessitating new approaches to lifelong management.

As patients age, some may begin to manage their own healthcare, making physician-guided transition to the adult setting critical.3 Physicians should ensure the following:

The transition from paediatric to adult care and long-term adult care are critical areas to address in care plans for adolescent and adult patients.3 Long-term care considerations are ideally best addressed in a centre with significant MPS experience, and they require careful coordination across specialities.3,17 Long-term issues include but are not limited to the following:

Long-term management of MPS disorders, including ongoing assessments and a site-specific transition strategy from paediatric to adult care, may lead to sustained improvement in quality of life and a better future for your patients.3,17–19

Because clinical manifestations of mucopolysaccharidosis (MPS) disorders are multisystemic, a patient-specific, multidisciplinary approach is required to proactively recognise and manage complications such as orthopaedic surgeries, which are frequent in patients with MPS.1,2

Patients with MPS disorders typically have a number of surgical interventions over their lifetimes. A natural history study assessing a cohort of 325 patients with Morquio A (MPS IVA) found that over 70% of patients had at least one surgical procedure.3

Patients with MPS have a high perisurgical mortality rate due to multiple factors, including upper and lower airway obstruction, cervical spinal instability, respiratory impairment, cardiovascular morbidities, and frequent infections.4 For example, surgical complications resulted in an 11% mortality rate in patients with Morquio A (n=27).5

Imaging modality selection for evaluation of spinal involvement is critical; a table comparing the strengths and limitations of MRI, CT, and radiography is presented belowting patients with MPS.4

Preparing for surgical and anaesthetic risk in patients with MPS requires an experienced, multidisciplinary care team consisting of anaesthesiology, cardiology, pulmonology, and otolaryngology specialists.4

Anaesthetic risk factors include the following, outlined in the figure below.

Surgical risk assessment and perioperative monitoring are fundamental components of a tailored surgical plan, and they can reduce the risks of negative surgical outcomes and mortality in patients with MPS.4,10,11

Considerations

MPS I

MPS III/IV/VI

References: 1. McGill J et al. Enzyme replacement therapy for mucopolysaccharidosis VI from 8 weeks of age – a sibling control study. Clin Genet. 2010;77(5):492–498. 2. Furujo M et al. Enzyme replacement therapy attenuates disease progression in two Japanese siblings with mucopolysaccharidosis type VI. Mol Genet Metab. 2011;104(4):597–602. doi:10.1016/j.ymgme.2011.08.029. 3. Clarke LA. Pathogenesis of skeletal and connective tissue involvement in the mucopolysaccharidoses: glycosaminoglycan storage is merely the instigator. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011;50(suppl 5):v13–18. 4. Lehman TJA et al. Diagnosis of the mucopolysaccharidoses. Rheumatology. 2011;50(suppl 5):v41–v48. 5. Morishita K et al. Musculoskeletal manifestations of mucopolysaccharidoses. Rheumatology. 2011;50(suppl 5):v19–v25. 6. Muenzer J, Beck M, Eng CM, et al.Genet Med. 2011;13(2):95–101. doi:10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181fea459. 7. Hendriksz C Improved diagnostic procedures in attenuated mucopolysaccharidosis. Br J Hosp Med 2011;72(2):91–95. 8. Muenzer J. Early initiation of enzyme replacement therapy for the mucopolysaccharidoses. Mol Genet Metab 2014;111(2):63–72. 9. Hendriksz CJ et al. International guidelines for the management and treatment of Morquio A syndrome. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2014;9999A:1–15. 10. Bagewadi S et al. Home treatment with Elaprase® and Naglazyme® is safe in patients with mucopolysaccharidoses types II and VI, respectively. J Inherit Metab Dis 2008;31(6):733-737. 11. BioMarin Pharmaceutical Inc. VIMIZIM website. http://www.vimizim.com/. Accessed December 21, 2015. 12. BioMarin Pharmaceutical Inc. NAGLAZYME website. http://www.naglazyme.com/. Accessed December 21, 2015. 13. Muenzer J et al. International Consensus Panel on the Management and Treatment of Mucopolysaccharidosis I. Mucopolysaccharidosis I: management and treatment guidelines. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):19–29.

References: 1. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Defining the PCMH. https://pcmh.ahrq.gov/page/defining-pcmh. Accessed December 15, 2015. 2. Muenzer J. The mucopolysaccharidoses: a heterogeneous group of disorders with variable pediatric presentations. J Pediatr 2004;144(suppl 5):S27–S34. 3. Hendriksz CJ et al. et al. International guidelines for the management and treatment of Morquio A syndrome. Am J Med Genet Part A 2014;9999A:1–15. 4. White KK. Orthopaedic aspects of mucopolysaccharidoses. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011;50(suppl 5):v26–v33. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/ker393. 5. Walker R et al. Anaesthesia and airway management in mucopolysaccharidosis. J Inherit Metab Dis 2013;36(2):211–219. 6. Harmatz P et al. The Morquio A clinical assessment program: baseline results illustrating progressive, multisystemic clinical impairments in Morquio A subjects. Mol Genet Metab 2013;109(1):54–61. 7. Muenzer J et al. International Consensus Panel on the Management and Treatment of Mucopolysaccharidosis I. Mucopolysaccharidosis I: management and treatment guidelines. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):19–29. 8. Morishita K et al. Musculoskeletal manifestations of mucopolysaccharidoses. Rheumatology. 2011;50(suppl 5):v19–v25. 9. Hendriksz C. Improved diagnostic procedures in attenuated mucopolysaccharidosis. Br J Hosp Med. 2011;72(2):91–95. 10. White KK et al. Mucopolysaccharide disorders in orthopaedic surgery. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013;21:12–22. 11. Valayannopoulos V et al. Therapy for the mucopolysaccharidoses. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011;50 Suppl 5:v49–59. 12. Solanki GA et al. Spinal involvement in mucopolysaccharidosis IVA (Morquio-Brailsford or Morquio A syndrome): presentation, diagnosis and management. J Inherit Metab Dis 2013;36(2):339-355. 13. Spinello CM et al. Anesthetic management in mucopolysaccharidoses. ISRN Anesthesiol. 2013;2013:1–10. 14. Neufeld EF, Muenzer J. In: Valle Det al. The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2001:3421–3452. 15. Scarpa M, Almassy Z, Beck M et al.Mucopolysaccharidosis type II: European recommendations for the diagnosis and multidisciplinary management of a rare disease. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2011;6:72. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-6-72. 16. James A et al. The oral health needs of children, adolescents and young adults affected by a mucopolysaccharide disorder. JIMD Rep. 2012;2:51–58. 17. Coutinho MF et al. Glycosaminoglycan storage disorders: a review. Biochem Res Int. 2012;2012:471325. 18. Kakkis ED et al.The mucopolysaccharidoses. In: Berg BO, ed. Principles of child neurology. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1996:1141–1166. 19. Lehman TJA et al. Diagnosis of the mucopolysaccharidoses. Rheumatology. 2011;50(suppl 5):v41–v48.

References: 1. Hendriksz CJ et al. International guidelines for the management and treatment of Morquio A syndrome. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2014;9999A:1–15. 2. Muenzer J, Beck M, Eng CM, et al.Genet Med. 2011;13(2):95–101. doi:10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181fea459. 3. Harmatz P et al. The Morquio A clinical assessment program: baseline results illustrating progressive, multisystemic clinical impairments in Morquio A subjects. Mol Genet Metab. 2013;109(1):54–61. 4. Walker R et al. Anaesthesia and airway management in mucopolysaccharidosis. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2013;36(2):211–219. 5. Lavery C, Hendriksz C. Mortality in patients with Morquio syndrome A. J Inherit Metab Dis Rep 2015;15:59–66. 6. Theroux MC et al.Anesthetic care and perioperative complications of children with Morquio syndrome. Paediatr Anaesth. 2012;22(9):901–907. 7. Muenzer J. The mucopolysaccharidoses: a heterogeneous group of disorders with variable pediatric presentations. J Pediatr 2004;144(suppl 5):S27–S34. 8. Scarpa M et al. Mucopolysaccharidosis type II: European recommendations for the diagnosis and multidisciplinary management of a rare disease. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2011;6:72. 9. Valayannopoulos V et al. Therapy for the mucopolysaccharidoses. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011;50 Suppl 5:v49–59. 10. Solanki GA et al. Spinal involvement in mucopolysaccharidosis IVA (Morquio-Brailsford or Morquio A syndrome): presentation, diagnosis and management. J Inherit Metab Dis 2013;36(2):339–355. 11. Vitale MG et al. Delphi Consensus Report: Best practices in intraoperative neuromonitoring in spine deformity surgery: development of an intraoperative checklist to optimize response. Spine Deformity. 2014;2(5):333–339. 12. Solanki GA et al. A multinational, multidisciplinary consensus for the diagnosis and management of spinal cord compression among patients with mucopolysaccharidosis VI. Mol Genet Metab 2012;107:15–24. 13. Spinello CM et al. Anesthetic management in mucopolysaccharidoses. ISRN Anesthesiol. 2013;2013:1–10. 14. White KK et al. Mucopolysaccharide disorders in orthopaedic surgery. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013;21:12–22.