Register for access

Discover more online at MPSmeetings.com. Unlock exclusive content, listen to expert-led podcasts, watch on-demand webinars and much more.

In many genetic conditions, diagnostic delay is common due to lack of clinical suspicion.

Presentation and disease progression are unpredictable, multisystemic and variable across and within MPS disorders, making diagnosis challenging.1

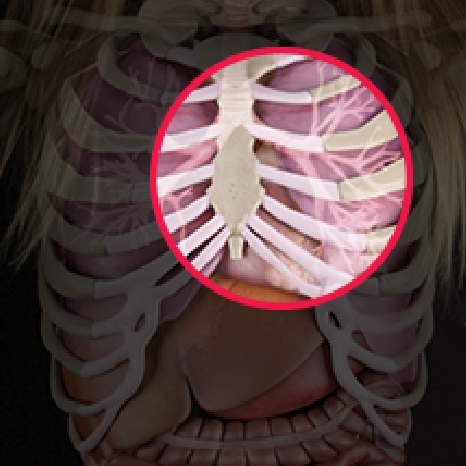

Watch how MPS affects patients from the inside out. As an example, this video illustrates the mechanism of disease for Morquio A (MPS IVA).

Discover more online at MPSmeetings.com. Unlock exclusive content, listen to expert-led podcasts, watch on-demand webinars and much more.

Often mischaracterised as either purely a childhood disorder or a musculoskeletal disease, MPS might not be as uncommon as you think.

MPS disorders are complex, multisystemic conditions whose unique risks and life–altering complications require careful, coordinated care from a multidisciplinary team of specialists.1-5 The emergence of specific therapies for some MPS disorders has elevated the critical nature of early intervention and diagnosis as key components of optimal, long-term outcomes.1,2,3,6,7