Supportive clinical evidence from sibling studies suggests that early intervention provides multiple opportunities to improve patient outcomes through disease-specific management and early initiation of ERT, if available.1-6

ERT, whether initiated early or later in life, has been shown to improve key clinical parameters, such as endurance and pulmonary measures, which are critical to quality of life, maintenance of ambulation and activities of daily living.7,8

You are now leaving the MPSReference website. Please choose a link below to be redirected to more information on specific available enzyme replacement therapies.

Vimizim.com for treatment of Morquio A

Naglazyme.com for treatment of MPS VI

For additional information on clinical trials, visit www.clinicaltrials.gov.

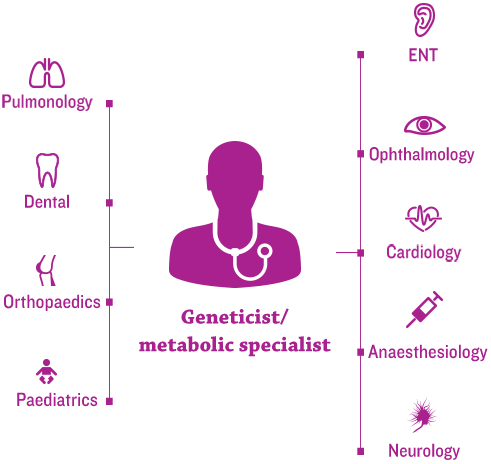

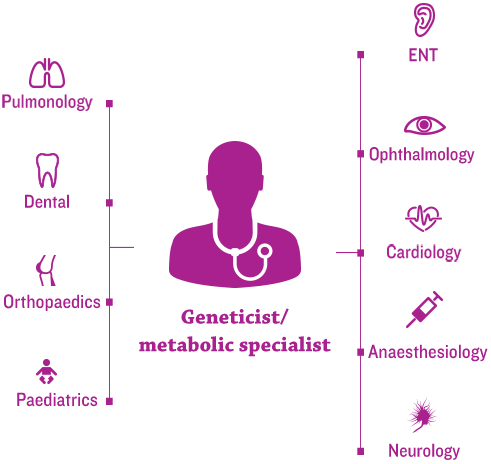

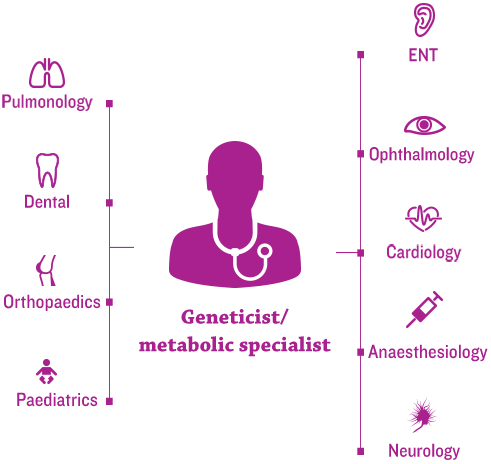

The new era of management for progressive, complex, genetic conditions, such as mucopolysaccharidosis (MPS) disorders, hinges on the efficient coordination of each patient’s healthcare team.1

Geneticists and/or metabolic specialists are typically at the centre and help to coordinate multidisciplinary care and an individualised management plan.2,3

Given the high surgical burden of patients with MPS, which is complicated by the systemic nature of the disease, anaesthesiologists and the operative-care team are essential members of the multidisciplinary medical team.4,5

Many MPS disorders have available management guidelines and speciality-specific consensus recommendations regarding lifelong management of MPS. Guidelines typically recommend:3,6

Early and ongoing assessments from a coordinated care team can improve patient outcomes and may help prevent irreversible damage.6

Skeletal and multisystemic effects of MPS increase the risk of perioperative morbidity and mortality, making ongoing assessment and monitoring essential to decrease the risk of surgical and anaesthetic complications.5,8 Airway obstruction and pulmonary oedema are among the most significant anaesthetic complications, sometimes requiring emergency tracheotomy or reintubation, which can be very challenging.5

Patients with MPS are at elevated risk of complications from anaesthetic and procedural sedation. When possible, general anaesthesia should be avoided and, when necessary, administered only by experienced anaesthesiologists.8,9

Procedural risk associated with necessary sedation and anaesthesia is a critical consideration in imaging modality selection for assessing spinal involvement.8

For anaesthesiologists managing anaesthetic care in patients with MPS, consideration should be given to the specific systemic complications presented by the different types of MPS, notably spinal cord compression and airway obstruction.8

Preparing for surgical and anaesthetic risk in patients with MPS requires an experienced, multidisciplinary care team consisting of anaesthesiology, cardiology, pulmonology, and otolaryngology.5

Anaesthetic risk factors include the following:

Operative care considerations across a coordinated team are critical to reducing negative surgical outcomes.5 The table below illustrates these considerations.

The anaesthetic risk in patients with MPS is considered high for many reasons, including airway abnormalities, orthopaedic deformities, pulmonary predisposition, and cardiac and neurological involvement.9 Of note, certain MPS disorders may demonstrate greater risk than others, as seen in the table below.

MPS subtype and severity are important indicators of anaesthetic risk and should be taken into consideration prior to surgery. Operative risk is higher in MPS I, II, IV, and VI, with an overall mortality rate of 20%.9

Frequency of assessments and involvement of specific specialists vary across the different MPS types. For patients with MPS diseases associated with primary neurodegenerative and cognitive complications, such as MPS I, II, and III, additional and regular neurobehavioural and psychiatric evaluations are recommended.6,12,13

In addition to speciality-specific assessments that should be done to facilitate positive long-term outcomes for patients with MPS, important steps can be taken by the coordinating physician, typically the geneticist and/or metabolic specialist, related to general health. Their role in educating other healthcare professionals (e.g. dentists, physiotherapists, paediatricians, family doctors) and families about the disease and general management strategies is critical and should include the following3:

Speciality-specific assessments, as well as regular physical examinations and overall health interventions, should follow recommended guidelines, which may vary among MPS subtypes.3

Improvements in the treatment of MPS disorders are contributing to long-term outcomes for patients, necessitating new approaches to lifelong management.

As patients age, some may begin to manage their own healthcare, making physician-guided transition to the adult setting critical.3 Physicians should ensure the following:

The transition from paediatric to adult care and long-term adult care are critical areas to address in care plans for adolescent and adult patients.3 Long-term care considerations are ideally best addressed in a centre with significant MPS experience, and require careful coordination across specialities.3,15 Long-term issues include but are not limited to the following

Long-term management of MPS disorders – including ongoing assessments and a site-specific transition strategy from paediatric to adult care – may lead to sustained improvement in quality of life and a better future for your patients.3,15-17

Because clinical manifestations of mucopolysaccharidosis (MPS) disorders are multisystemic, a patient-specific, multidisciplinary approach is required to proactively recognise and manage complications. The administration of anaesthesia should be performed only in specialised centres by experienced anaesthesiologists and trained personnel. Indication for surgery should be carried out only after consulting the anaesthesiologist, who has the duty to discuss risks and benefits with patients and their families.1

Patients with MPS disorders typically have a number of surgical interventions over their lifetimes. A natural history study assessing a cohort of 325 patients with Morquio A (MPS IVA) found that over 70% of patients had at least one surgical procedure.2

Patients with MPS have a high perisurgical mortality rate due to multiple factors, including upper and lower airway obstruction, cervical spinal instability, respiratory impairment, cardiovascular morbidities, and frequent infections.2-4 For example, surgical complications resulted in an 11% mortality rate in patients with Morquio A (n=27).5

Creating a surgical plan is crucial and involves a multidisciplinary team of specialists who are, ideally, also experienced in treating patients with MPS.3

Due to the elevated risk of surgical and anaesthetic complications, it is essential to be aware of best practices in surgical preparation and perioperative care specific to MPS. Standard preoperative preparation is insufficient and ineffective for patients with MPS. A complete evaluation of each patient’s specific case must be performed in order to successfully plan for and execute procedures requiring anaesthesia.1

Postoperative monitoring and thorough reassessment is necessary even if patients show sustained improvement following the first year of surgery, as further glycosaminoglycan (GAG) deposition may have altered airway anatomy and cardiac and pulmonary function.1

Accurate preoperative examination requires a variety of analyses1:

General anaesthesia is dangerous and should generally be avoided; local anaesthesia with peripheral blocks is preferred whenever possible. Additionally, in order to reduce the risks associated with exposure to multiple anaesthetics, combining two or more diagnostic/surgical interventions during one episode of anaesthesia is advised.1

Postoperative treatment includes steroid prophylaxis to reduce oedema, standard treatment for patients with upper airway obstruction (bilateral positive airway pressure, continuous positive airway pressure), and continuous monitoring of respiratory and cardiac function.1

When emergency surgery is needed, guidelines used for patients with suspected cervical spine injury should be followed.1

Surgical risk assessment and perioperative monitoring are fundamental components of a tailored surgical plan, and they can reduce the risks of negative surgical outcomes and mortality in patients with MPS.3,9,10

References: 1. McGill JJ, Inwood AC, Coman DJ, et al. Enzyme replacement therapy for mucopolysaccharidosis VI from 8 weeks of age—a sibling control study. Clin Genet. 2010;77(5):492–498. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0004.2009.01324.x. 2. Furujo M, Kubo T, Kosuga M, Okuyama T. Enzyme replacement therapy attenuates disease progression in two Japanese siblings with mucopolysaccharidosis type VI. Mol Genet Metab. 2011;104(4):597–602. doi:10.1016/j.ymgme.2011.08.029. 3. Clarke LA. Pathogenesis of skeletal and connective tissue involvement in the mucopolysaccharidoses: glycosaminoglycan storage is merely the instigator. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011;50(suppl 5):v13–18. 4. Lehman TJA, Miller N, Norquist B, Underhill L, Keutzer J. Diagnosis of the mucopolysaccharidoses. Rheumatology. 2011;50(suppl 5):v41–v48. 5. Morishita K, Petty RE. Musculoskeletal manifestations of mucopolysaccharidoses. Rheumatology. 2011;50(suppl 5):v19–v25. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/ker397. 6. Muenzer J, Beck M, Eng CM, et al.Genet Med. 2011;13(2):95–101. doi:10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181fea459. 7. Hendriksz C. Improved diagnostic procedures in attenuated mucopolysaccharidosis. Br J Hosp Med. 2011;72(2):91-95. 8. Muenzer J. Early initiation of enzyme replacement therapy for the mucopolysaccharidoses. Mol Genet Metab. 2014;111(2):63–72. doi:10.1016/j.ymgme.2013.11.015. 9. Hendriksz CJ, Berger KI, Giugliani R, et al. International guidelines for the management and treatment of Morquio A syndrome. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2014;9999A:1–15. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.36833. 10. Bagewadi S, Roberts J, Mercer J, Jones S, Stephenson J, Wraith JE. Home treatment with Elaprase® and Naglazyme® is safe in patients with mucopolysaccharidoses types II and VI, respectively. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2008;31(6):733–737. doi:10.1007/s10545-008-0980-0. 11. BioMarin Pharmaceutical Inc. VIMIZIM Web site. http://www.vimizim.com/. Accessed December 21, 2015. 12. BioMarin Pharmaceutical Inc. Naglazyme Web site. http://www.naglazyme.com/. Accessed December 21, 2015. 13. Muenzer J, Wraith JE, Clarke LA, International Consensus Panel on the Management and Treatment of Mucopolysaccharidosis I. Mucopolysaccharidosis I: management and treatment guidelines. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):19–29. doi:10.1542/peds.2008-0416.

References: 1. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Defining the PCMH. https://pcmh.ahrq.gov/page/defining-pcmh. Accessed December 15, 2015. 2. Muenzer J. The mucopolysaccharidoses: a heterogeneous group of disorders with variable pediatric presentations. J Pediatr. 2004;144(suppl 5):S27–S34. 3. Hendriksz CJ, Berger KI, Giugliani R, et al. International guidelines for the management and treatment of Morquio A syndrome. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2014;9999A:1–15. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.36833. 4. Harmatz P, Mengel KE, Giugliani R, et al. The Morquio A clinical assessment program: baseline results illustrating progressive, multisystemic clinical impairments in Morquio A subjects. Mol Genet Metab. 2013;109(1):54–61. doi:10.1016/j.ymgme.2013.01.021. 5. Walker R, Belani KG, Braunlin EA, et al. Anaesthesia and airway management in mucopolysaccharidosis. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2013;36(2):211–219. doi:10.1007/s10545-012-9563-1. 6. Muenzer J, Wraith JE, Clarke LA, International Consensus Panel on the Management and Treatment of Mucopolysaccharidosis I. Mucopolysaccharidosis I: management and treatment guidelines. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):19–29. doi:10.1542/peds.2008-0416. 7. Vitale MG, Skaggs DL, Pace GI, et al. Delphi Consensus Report: Best practices in intraoperative neuromonitoring in spine deformity surgery: development of an intraoperative checklist to optimize response. Spine Deformity. 2014;2(5):333–339. doi:10.1016/j.jspd.2014.05.003. 8. Solanki GA, Martin KW, Theroux MC, et al. Spinal involvement in mucopolysaccharidosis IVA (Morquio-Brailsford or Morquio A syndrome): presentation, diagnosis and management. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2013;36(2):339–355. doi:10.1007/s10545-013-9586-2. 9. Spinello CM, Novello LM, Pitino S, et al. Anesthetic management in mucopolysaccharidoses. ISRN Anesthesiol. 2013;2013:1–10. doi:10.1155/2013/791983. 10. Theroux MC, Nerker T, Ditro C, Mackenzie WG. Anesthetic care and perioperative complications of children with Morquio syndrome. Paediatr Anaesth. 2012;22(9):901–907. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9592.2012.03904.x. 11. Solanki GA, Alden TD, Burton BK, et al. A multinational, multidisciplinary consensus for the diagnosis and management of spinal cord compression among patients with mucopolysaccharidosis VI. Mol Genet Metab. 2012;107:15–24. doi:10.1016/j.ymgme.2012.07.018. 12. Neufeld EF, Muenzer J. The mucopolysaccharidoses. In: Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Valle D, eds. The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease. Vol 3. 8th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2002:2465–2494. 13. Scarpa M, Almassy Z, Beck M, et al. Mucopolysaccharidosis type II: European recommendations for the diagnosis and multidisciplinary management of a rare disease. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2011;6:72. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-6-72. 14. James A, Hendriksz CJ, Addison O. The oral health needs of children, adolescents and young adults affected by a mucopolysaccharide disorder. JIMD Rep. 2012;2:51–58. doi:10.1007/8904_2011_46. 15. Coutinho MF, Lacerda L, Alves S. Glycosaminoglycan storage disorders: a review. Biochem Res Int. 2012;2012:471325. doi:10.1155/2012/471325. 16. Kakkis ED, Neufeld EF. The mucopolysaccharidoses. In: Berg BO, ed. Principles of child neurology. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1996:1141–1166. 17. Lehman TJA, Miller N, Norquist B, Underhill L, Keutzer J. Diagnosis of the mucopolysaccharidoses. Rheumatology. 2011;50(suppl 5):v41-v48.

References: 1. Spinello CM, Novello LM, Pitino S, et al. Anesthetic management in mucopolysaccharidoses. ISRN Anesthesiol. 2013;2013:1–10. doi:10.1155/2013/791983. 2. Harmatz P, Mengel KE, Giugliani R, et al. The Morquio A clinical assessment program: baseline results illustrating progressive, multisystemic clinical impairments in Morquio A subjects. Mol Genet Metab. 2013;109(1):54–61. doi:10.1016/j.ymgme.2013.01.021. 3. Walker R, Belani KG, Braunlin EA, et al. Anaesthesia and airway management in mucopolysaccharidosis. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2013;36(2):211–219. doi:10.1007/s10545-012-9563-1. 4. Hendriksz CJ, Berger KI, Giugliani R, et al. International guidelines for the management and treatment of Morquio A syndrome. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2014;9999A:1–15. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.36833. 5. Lavery C, Hendriksz C. Mortality in patients with Morquio syndrome A. J Inherit Metab Dis Rep. 2015;15:59–66. doi:10.1007/8904_2014_298. 6. Theroux MC, Nerker T, Ditro C, Mackenzie WG. Anesthetic care and perioperative complications of children with Morquio syndrome. Paediatr Anaesth. 2012;22(9):901–907. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9592.2012.03904.x. 7. Muenzer J. The mucopolysaccharidoses: a heterogeneous group of disorders with variable pediatric presentations. J Pediatr. 2004;144(suppl 5):S27–S34. 8. Scarpa M, Almassy Z, Beck M, et al. Mucopolysaccharidosis type II: European recommendations for the diagnosis and multidisciplinary management of a rare disease. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2011;6:72. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-6-72. 9. Solanki GA, Martin KW, Theroux MC, et al. Spinal involvement in mucopolysaccharidosis IVA (Morquio-Brailsford or Morquio A syndrome): presentation, diagnosis and management. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2013;36(2):339–355. doi:10.1007/s10545-013-9586-2. 10. Vitale MG, Skaggs DL, Pace GI, et al. Delphi Consensus Report: Best practices in intraoperative neuromonitoring in spine deformity surgery: development of an intraoperative checklist to optimize response. Spine Deformity. 2014;2(5):333–339. doi:10.1016/j.jspd.2014.05.003.